THE SAD GIRL

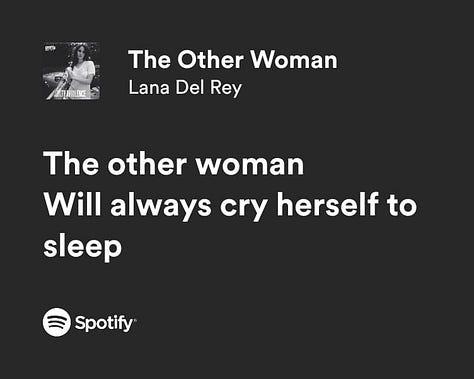

The sad girl is not just a cultural archetype but a mood, a way of being that feels both ephemeral and deeply rooted. She exists in the digital age as a figure of contradiction: achingly self-aware yet cloaked in mystery, vulnerable yet performative, intimate yet curated. The sad girl wears her pain like silk—delicate, shimmering in certain lights, and just out of reach. She lives in fleeting glimpses: a quiet confession on Twitter, a Polaroid of smudged eyeliner, a Spotify playlist titled something like songs to cry to in the bath.

She is a product of our time, born from the digital age’s peculiar ability to make the personal public. Social media, with its endless scroll of curated lives, has offered a stage for sadness to unfold in ways that feel both radical and deeply commodified. Where once sorrow might have been whispered to a friend or scribbled into a journal, it now lives in pixels, broadcast to anyone who might care to listen.

Platforms like Tumblr, Instagram, and TikTok have played a pivotal role in shaping this identity. Tumblr, in particular, was the birthplace of a certain kind of online melancholy, a world of faded imagery and cryptic text posts that made sadness feel romantic, even aspirational. A photo of a cigarette burning down to its filter, a line of Sylvia Plath typed in Courier font, a grainy picture of the ocean at dusk—these weren’t just images; they were symbols of a collective longing, a shared understanding that life was beautiful precisely because it hurt.

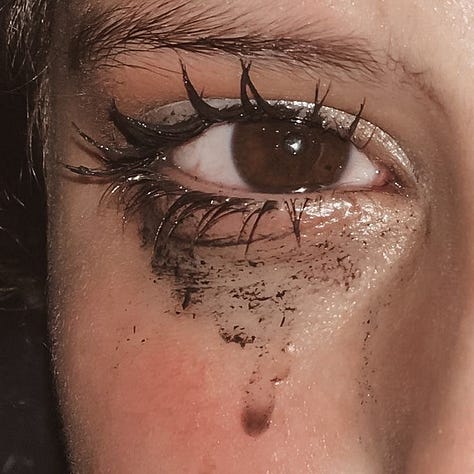

As social media evolved, so too did the sad girl. Instagram brought a glossy sheen to her sorrow, turning what was once raw into something artful. A sad girl might post a photo of herself bathed in soft light, her mascara smeared like it was painted there, a caption reading something like, “Some days the sky feels heavier than others.” TikTok, with its chaotic vibrancy, gave her new forms of expression: a teary-eyed confessional set to Phoebe Bridgers’ Funeral, or a 15-second montage of melancholic moments, soundtracked by Lana Del Rey’s Born to Die.

But the rise of the sad girl is not merely about aesthetics; it’s also a response to the world we live in. Social media thrives on extremes: the happiest moments, the funniest jokes, the most heart-wrenching confessions. And in this landscape, sadness feels like an antidote to the relentless cheeriness of curated perfection. It cuts through the noise, offering something raw and human in a space that often feels anything but.

The sad girl’s allure lies in her honesty, or at least the illusion of it. She seems to say, I am not afraid to feel this deeply. I am not afraid to fall apart. Her sadness becomes a form of resistance in a world that values productivity, resilience, and endless optimisation. To exist as a sad girl is to reject the pressure to always be fine, to lean into the messiness of being human.

And yet, there is a tension in this vulnerability, a fine line between authenticity and performance. The sad girl’s tears may be real, but they are also captured through the lens of a front-facing camera. Her heartbreak may be genuine, but it is also edited to fit the aesthetic of her grid. Social media doesn’t just invite us to share our lives; it asks us to package them, to turn our pain into something digestible, something beautiful.

This tension is perhaps the defining feature of the sad girl: her sadness is both deeply felt and deliberately crafted. It is a performance, yes, but it is also real. In this way, she mirrors the paradox of our digital selves, where the line between who we are and who we present to the world is increasingly blurred.

The sad girl came to be because we needed her. We needed someone to remind us that it’s okay to feel lost, to grieve, to long for something unnamed. But as she’s evolved, she’s also become a reflection of our age—of the ways we commodify even our most private emotions, of the strange intimacy that comes from sharing our lives with strangers online, of the longing for connection that hums beneath every post and caption.

She sits, perhaps, on a windowsill somewhere, gazing out at the rain, a cigarette dangling from her fingers. Or maybe she’s staring at her phone in the dark, the glow of the screen lighting her face. In both cases, she is not just a person but a symbol, a mood, a way of saying what words so often fail to express: This hurts, and I don’t know what to do with it, but at least I’m not alone.

HER HISTORY

To understand the sad girl of today, we must trace her lineage through the veins of history. Sadness, after all, is no new visitor to the human soul. Long before it was distilled into hashtags and filtered photographs, it lingered in the pages of poetry, in the whispers of philosophers, and in the silence of candlelit rooms. Our relationship with sadness has always been complex—at times revered, at times feared, and at times hidden beneath the masks we wear to face the world.

The ancient Greeks, with their relentless pursuit of understanding, were among the first to name it. They called it melancholia, a word that evokes depth and darkness, meaning ‘black bile’. To them, sadness was not just an emotion but a condition, a temperament shaped by the delicate balance of the body’s humors. Aristotle believed that those prone to melancholy possessed a particular brilliance, an ability to see the world more clearly, to grasp its beauty and its pain in equal measure. Melancholy, he thought, was the price one paid for genius. And so, sadness was not something to be avoided or dismissed—it was a mark of depth, a sign of greatness.

But as the centuries turned, the view darkened.

In the medieval world, sadness took on a more sinister shape. It was no longer a reflection of the mind’s complexity but a moral failing, a sign of spiritual weakness. The Church saw sadness—particularly prolonged sadness—as a danger, a gateway to despair, which was considered a sin against God. To feel sorrow was to doubt the divine, to turn away from grace. Remedies for sadness came in the form of prayer and penance, a desperate attempt to purge the soul of its heaviness. There was no room for indulgence in sorrow, no space for the quiet contemplation of grief.

It wasn’t until the Renaissance and, later, the Romantic era that sadness began to reclaim its place as something more than a flaw. The Romantics, in particular, embraced sorrow as a vital part of the human experience. To feel deeply—even painfully—was to live fully. Poets like John Keats, Lord Byron, and Mary Shelley found beauty in despair, crafting verses that lingered on the ache of existence. Keats wrote of the “wakeful anguish of the soul,” while Byron declared, “Sorrow is knowledge.” For them, sadness was not something to be banished but something to be explored, a source of creativity and meaning.

‘Sorrow is knowledge: they who know the most

Must mourn the deepest o’er the fatal truth,

The Tree of Knowledge is not that of Life.’

The Romantics gave us permission to linger in sadness, to find in it a kind of sublime beauty. Their work echoed with the belief that sorrow could illuminate the world, casting it in a sharper, more poignant light. This was sadness not as weakness but as a gift—a painful, necessary gift that brought us closer to truth.

But even as sadness was celebrated in art and literature, the world around it continued to shift. By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the rise of psychology began to reshape our understanding of sorrow once again. Sadness was no longer seen as a spiritual or artistic condition; it was a medical one, something to be diagnosed and treated. The advent of terms like “depression” and “neurasthenia” marked a new era in which sadness became a problem to be solved, a malady to be cured.

This medicalisation of sadness brought with it both progress and limitation. On the one hand, it allowed for the development of treatments and therapies, a recognition that prolonged sadness could be a serious and debilitating condition. On the other hand, it introduced the idea that sadness was something unnatural, something to be fixed rather than felt.

And yet, through all these transformations, sadness remained. It lingered in quiet rooms and forgotten corners, in sonnets and symphonies, in the way the light falls just so on a winter’s afternoon. It survived the centuries because it is, and has always been, a part of what it means to be human.

The sad girl of today carries this history with her, even if she doesn’t realise it. She is the descendant of Aristotle’s melancholic geniuses, of the medieval penitent, of the Romantic poet staring out at a windswept landscape. Her sadness is not new; it is eternal, shaped by time and culture but never fully contained by them.

What makes her different is the world she inhabits—a world of endless connection and endless comparison, where sadness is both shared and commodified, performed and consumed. The sad girl exists at a crossroads, caught between history and modernity, between the private and the public, between authenticity and artifice.

But perhaps this is why she resonates so deeply. She reminds us that sadness is not just an emotion—it is a story, one that has been told and retold through the ages, a thread that connects us to those who came before. And in a world that often demands perfection, she gives us permission to sit with our sorrow, to feel it fully, to let it wash over us like a wave.

For all the ways the sad girl has been shaped by history, she also shapes it in return. She is not just a reflection of the past; she is a mirror held up to the present, asking us to confront the ways we live, the ways we share, and the ways we feel. And in that reflection, we may find something quietly profound: the reminder that sadness, like all things, is fleeting—but it is also deeply, beautifully human.

this was such a comforting read! the amount of thought you put into this post was evident in every paragraph. so beautifully written as alwayssss

as always, your work is profound and beautiful. I enjoy your writing style a lot- the way that you meticulously use vivid imagery as an instrument at your disposal. What you said about how sadness has turned into something to be treated rather than something to be felt, was so beautiful. great work! 🤍